JAMES GRAHAM EARL OF MONTROSE 1612-1650 |

|

James Graham inherited the earldom of Montrose from his father in 1626. He was educated at St. Andrew's University where he became inspired by classical tales of military glory. In November 1629, he married Magdalene Carnegie, daughter of Lord Carnegie of Kinnaird. After the birth of his first two sons, Montrose went to France and Italy to complete his education, which included a period at the French military academy at Angers. He returned to Scotland in 1637 and became active in the revolt against the imposition of Archbishop Laud's prayer book on the Scottish Kirk, signing the National Covenant in February 1638. In July, Montrose went with covenanting lairds and clergymen to Aberdeen, where he tried unsuccessfully to persuade the "Aberdeen Doctors" of the university to sign the Covenant. In November 1638, he attended the Glasgow Assembly, which defied the King by abolishing Episcopacy and establishing presbyterian church government in Scotland. Montrose gained his first military experience leading Covenanter troops in the First Bishops' War. He drove the Marquis of Huntly out of Aberdeen in March 1639 and campaigned against Huntly's clan the Gordons. In June, Huntly's younger son Viscount Aboyne sailed into Aberdeen harbour in one of the King's warships and occupied the town. Montrose returned with artillery and bombarded the Royalists at Brig of Dee, forcing Aboyne and the Gordons to flee. After the signing of the Pacification of Berwick, Montrose came into conflict with Archibald Campbell, Earl of Argyll, suspecting him of trying to usurp the power of the King in Scotland for his own ends. He also distrusted the Marquis of Hamilton, who appeared to be in league with Argyll. Montrose drew up a secret agreement with like-minded Covenanters known as the Cumbernauld Bond. Adherents |

undertook to defend the true principles of the Covenant against the machinations of Argyll and his supporters. Some suspected that Montrose had become a Royalist, but he was granted the honour of leading the first regiment of Covenanters across the River Tweed when the Scots invaded England in the Second Bishops' War (August 1640).

When the war was over, Montrose's criticisms of Argyll and his intercepted correspondence with King Charles resulted in his arrest on charges of conspiracy against the ruling Committee of Estates. In June 1641, he was imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle. When King Charles visited Scotland to finalise the treaty with England, Montrose demanded an open trial. Anxious to maintain their new alliance, neither the King nor the Estates would agree to this, but Montrose was released on bail in November 1641. He then retired from public life until the outbreak of the English Civil War when he attempted to rally Scottish support for the King. Montrose opposed the Solemn League and Covenant, which secured an alliance between Scotland and the English Parliamentarians, and joined King Charles at Oxford in 1643. His loyalty to the King and the Royalist cause was passionate and unwavering throughout the rest of his career. |

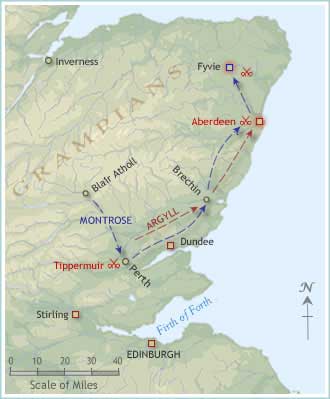

When Lord Leven's Covenanter army invaded England in 1644, the King appointed Montrose his Lieutenant-General in Scotland. Montrose planned to start a war against the Covenanters north of the border that would distract their forces in England, but no Royalist troops could be spared for the venture. In July 1644, a small band of Irish Confederates, led by Alasdair MacColla, landed on the west coast of Scotland. They were sent by the Earl of Antrim, who had promised to supply King Charles with Irish troops. MacColla's band marched into the Highlands, terrorising the covenanting Campbell clan as they went. Montrose located MacColla at Blair Atholl where he raised his standard as the King's deputy on 28 August 1644. With MacColla's Irishmen and a motley band of clansmen as the nucleus of his army, Montrose began a spectacular Royalist campaign against the Covenanters in the Highlands. He defeated Lord Elcho at Tippermuir in September 1644 then captured and sacked Aberdeen. King Charles created him Marquis of Montrose and Earl of Kincardine in November 1644. The Covenanters put a price on his head, dead or alive. Early in 1645, Montrose and MacColla led a guerrilla campaign against the Campbells and their chief, the Marquis of Argyll. |

| They struck deep into Campbell territory and inflicted a grievous defeat on the clan at the battle of Inverlochy in February 1645, breaking their power in the western Highlands. According to plan, Covenanter regiments were withdrawn from Lord Leven's army in England and returned to Scotland to deal with Montrose, thus weakening Leven in the field and undermining Covenanter political influence in London. After plundering Dundee in April 1645, Montrose was pursued back into the Highlands by Major-General Baillie. Constantly outwitting the Covenanters, he defeated Colonel Hurry at Auldearn in May 1645 and Baillie at Alford in June. In August 1645, Montrose achieved his greatest victory when he defeated Baillie and the Covenanter Committee of War headed by Argyll at the battle of Kilsyth, which left him for a short time master of Scotland. Montrose's victories in Scotland kept up the morale of the Royalists in England. The King's main strategic objective after the defeat at Naseby was to join forces with him. When Montrose moved into the Lowlands, however, his troops began to desert. He was defeated by superior Covenanter forces under David Leslie at Philliphaugh in September 1645 and his followers were massacred. Montrose remained in Scotland for another year but he was unable to pose a serious threat to the Covenanters again. |

|

In July 1646, King Charles, having surrendered himself to the Covenanters, ordered Montrose to cease hostilities.

Montrose sailed into exile on 3 September 1646. An account of his victories, written in Latin by George Wishart, made Montrose a hero throughout Europe. He was offered an appointment as lieutenant-general in the French army; the Emperor Ferdinand III awarded him the rank of field marshall, but Montrose remained devoted to the service of King Charles. He swore vengeance after the King's execution in January 1649 and immediately transferred his loyalty to Charles II, who was proclaimed King of Scots in February 1649. Charles appointed Montrose his captain-general in Scotland and authorised him to negotiate for military aid with European powers. Montrose travelled through Germany, Poland and Scandinavia attempting to raise forces for the King. To Montrose's dismay, Charles also entered into negotiations with the Covenanters. When talks broke down in May 1649, Charles attempted to coerce the Covenanters by ordering Montrose to take control of Scotland by military force. Montrose sent a small force of German and Danish mercenaries as an advance guard to occupy the Orkneys in September 1649 and joined them with reinforcements in March 1650. By the time Montrose landed on the Scottish mainland, Charles had re-opened negotiations with the Covenanters. Charles wrote to Montrose ordering him to disarm, but the orders never reached him. The Covenanters moved swiftly against him and Montrose was defeated at the battle of Carbisdale by Colonel Strachan in April 1650. A few days later, Charles disavowed Montrose under the terms of the Treaty of Breda. Montrose escaped into the mountains after Carbisdale. He fled to Ardvreck Castle on Loch Assynt where he was betrayed to the Covenanters by Neil MacLeod, laird of Assynt. Montrose was taken to Edinburgh and led through the streets in a cart driven by the hangman. Already under sentence of death for his campaign of 1644-5, Montrose was hanged at the Mercat Cross on 21 May 1650, protesting to the last that he was a true Covenanter as well as a loyal subject. Montrose's head was fixed on a spike at the Tolbooth in Edinburgh, his legs and arms were fixed to the gates of Stirling, Glasgow, Perth and Aberdeen. His dismembered body was buried in Edinburgh, but Lady Jean Napier had it secretly disinterred. The heart was removed, embalmed, placed in a casket, and sent to Montrose's exiled son as a symbol of loyalty and martyrdom. After the Restoration, Montrose's embalmed heart and bones were buried at the High Kirk of St Giles in Edinburgh in an elaborate ceremony with fourteen noblemen bearing the coffin (11 May 1661). Montrose's son James was confirmed in the inheritance of the Montrose titles. The marquisate became a dukedom in 1707. |

1644-5: Campaigns of the Marquis of Montrose |

In February 1644, shortly after the Covenanter invasion of England, James Graham, the Earl (later Marquis) of Montrose, was commissioned Lieutenant-General of the King's forces in Scotland. Montrose planned to incite a Royalist uprising north of the border to distract the Covenanter army in England. In April 1644, he persuaded the Marquis of Newcastle to lend a small force of 100 cavalry and dragoons under the command of Sir Robert Clavering to ride into Scotland and raise the Scottish nobility against the Covenanters. Montrose and Clavering crossed the border near Carlisle and occupied Dumfries on 14 April but no support was forthcoming. After the covenanting Earl of Callendar drove them out of Dumfries, Clavering insisted on returning to England with his cavalry. When they arrived back on Tyneside, Montrose and Clavering found that the main Covenanter army had by-passed the city of Newcastle and advanced to York. In early May, Montrose, now elevated to Marquis, attacked the Covenanter garrison at Morpeth, seizing the town around 10 May and ordering up artillery from Newcastle to besiege the castle, which surrendered on 29 May. Clavering and Sir Philip Musgrave meanwhile proceeded to harass Scottish garrisons south of the Tyne. However, the campaign in the north was eclipsed by the siege of York and the subsequent defeat of Prince Rupert and the northern Royalists at Marston Moor in July 1644. Montrose joined Rupert at Richmond in Yorkshire two days after the defeat. While Rupert withdrew to regroup his forces on the Welsh border, Montrose returned to Scotland. |

Tippermuir (Tibbermore), Perthshire, 1 September 1644 |

|

On 18 August 1644, the Marquis of Montrose crossed the border into Scotland in disguise accompanied by only two companions. He now accepted that the Covenanters in southern Scotland were too strong for local Royalists to risk an uprising and planned instead to raise the north-east Lowlands and the clans of the Highlands. Montrose had also heard that a band of 1,600 Irish Confederates sent by the Earl of Antrim had recently landed in western Scotland to fight for the King. Led by Alaisdair MacColla, the Irish advanced into the Highlands to join forces with Montrose at Blair Atholl in Perthshire where, on 30 August 1644, Montrose raised his standard as the King's deputy in Scotland. Montrose's army consisted of MacColla's 1,600 Irishmen and 800 Highlanders of the Stewart, Robertson and Graham clans who had been called out against MacColla but were persuaded to follow Montrose. The Committee of Estates in Edinburgh was slow to recognise the seriousness of the threat posed by Montrose and MacColla. Taking advantage of their lack of preparation, Montrose marched south-west from Blair Atholl towards Perth. The burgh was defended by Lord Elcho with a force of 6,000 foot and 700 horse, most of whom were local levies, newly-recruited and untrained. Elcho confronted Montrose on open ground at Tippermuir on the plain of Strathearn to the west of Perth on 1 September 1644. To avoid being outflanked by the much larger Covenanter force, Montrose drew up his troops in a line only three deep over a longer front than Elcho's, with MacColla's Irishmen in the centre. |

The Covenanter cavalry advanced against the Irish but were unnerved by their bloodcurdling battle cries. Montrose seized on their momentary hesitation to charge. As the Irish bore down upon them, most of Lord Elcho's infantry turned and ran. The cavalry tried to attack Montrose's flank but the Highlanders threw stones at them until they wheeled and fled, colliding with the Covenanter infantry that had stayed on the field and causing a general rout. Over 1,000 Covenanters were killed in the battle and rout; another 800 were taken prisoner. Montrose claimed to have lost only one man. The town of Perth surrendered immediately and a large quantity of weapons and supplies was captured. |

Aberdeen, 13 September 1644 |

After his victory at Tippermuir and the capture of Perth, the Marquis of Montrose received news that the Marquis of Argyll was marching from the west with a large Covenanter force. Anxious to keep up the momentum of his campaign, Montrose left Perth on 4 September 1644 and marched north-east along the Firth of Tay. The well-defended burgh of Dundee was summoned to surrender but refused, so Montrose continued towards Aberdeen. Although many of the Highland clansmen departed with their plunder after Tippermuir, Montrose was joined by the Earl of Airlie and other local lairds along the way. Montrose appeared before Aberdeen on 12 September with a force of around 1,500 Irish and Highland infantry and a small troop of 50 horse. On 13 September, the burgh was summoned to surrender. During the negotiations, a soldier from the Covenanter garrison is said to have shot and killed a drummer boy accompanying the heralds, infuriating Montrose and his troops who swore vengeance on the Covenanters of Aberdeen. Having refused the summons, the Covenanter garrison under the command of Lord Balfour of Burleigh marched out and deployed on a crest before the town with around 2,000 foot and 500 horse. Montrose divided his troops into three. The centre, armed only with dirks and claymores, were to charge the Covenanter infantry. Musketeers and two dozen horse on each wing were to hamper the Covenanter cavalry. Trusting to their superiority in cavalry, the Covenanters tried to outflank Montrose's forces and encircle them. The musketeers coolly let the Covenanter horse ride by, then turned about and opened fire. Cut off from their own infantry and with Montrose between them and the town, the cavalry fled the field. At the same time, MacColla and the Irishmen in the centre charged up the slope towards the Covenanter infantry, sending them fleeing back into Aberdeen. Montrose's forces poured in after them. The burgh of Aberdeen was subjected to a three-day orgy of murder, pillage and rape which Montrose made no attempt to stop. He may have wanted to make an example of Aberdeen for resisting him, but the atrocities committed there greatly damaged Montrose's cause. On hearing that the Marquis of Argyll's pursuing army was at Brechin, Montrose read the King's proclamation against the Covenant and withdrew towards the Highlands. While Alaisdair MacColla went to recruit in the west, the armies of Montrose and Argyll manoeuvred in the hills north-west of Aberdeen. On 27 October, Montrose occupied Fyvie Castle. For two days, the Royalists and Covenanters skirmished around the castle, but neither side could gain an advantage. After Argyll withdrew, Montrose marched back across the hills to Blair Atholl. |

Inverlochy, Inverness-shire, 2 February 1645 |

|

Alaisdair MacColla rejoined the Marquis of Montrose at Blair Atholl in late November 1644. MacColla had recruited more clansmen from among the MacDonalds, MacLeans and Camerons and was eager to strike at the Campbells. Although it was winter, he persuaded Montrose to mount a daring raid into the western Highlands. Taking advantage of unusually mild weather, Montrose and MacColla descended from the mountains to burn and plunder around the Campbell stronghold of Inverary Castle for several weeks during December 1644 and January 1645, putting Campbells mercilessly to the sword. By the end of January 1645, Montrose and MacColla had advanced north to Kilcumin (now Fort Augustus) in Inverness-shire where they learned that the Covenanters were marshalling their forces against them: Lord Seaforth with 5,000 men blocked their route north while to the south the Marquis of Argyll and the Campbells, reinforced by troops from Lord Leven's army in England, were at Inverlochy intent on revenge. Montrose and MacColla decided to double back to attack Argyll. On 31 January 1645, they led their 1,500 men on a bold flanking march through the frozen mountains. The Highlanders and Irishmen covered thirty miles of mountainous terrain in under thirty-six hours to descend on the Campbells at Inverlochy at the foot of Ben Nevis during the early hours of 2 February. The |

Marquis of Argyll, suffering from a dislocated shoulder, retired to his galley on Loch Linnhe leaving Sir Duncan Campbell of Auchinbreck in command of 2,000 Campbells and 1,500 Lowland infantry. Auchinbreck drew up his forces in front of Inverlochy Castle, with the Campbells in the centre flanked by Lowlanders on the two wings and a small reserve of Highlanders in the rear. Montrose deployed his 600 Highlanders in the centre and divided the Irishmen on the flanks, with Alaisdair MacColla on the right and Magnus O'Cahan on the left. He kept his small force of 20 cavalry in reserve. Montrose struck at dawn, before Auchinbreck could assess the position in daylight, with a swift, ferocious charge. On both flanks the Irish immediately routed the Lowlanders while the Highlanders clashed violently with the Campbells in the centre. The cavalry worked around to outflank the Campbells, scattered their reserve and blocked their retreat to the castle. Attacked from all sides, the Campbells were slaughtered by their bitter enemies of the Highland clans. Up to 1,700 Campbells were killed, including Auchinbreck who was beheaded personally by Alaisdair MacColla. The power of the Campbells in the Highlands was shattered. Having witnessed the massacre of his clansmen, the Marquis of Argyll escaped from the scene in his galley and fled to Edinburgh. |

Auldearn, Nairnshire, 9 May 1645 |

|

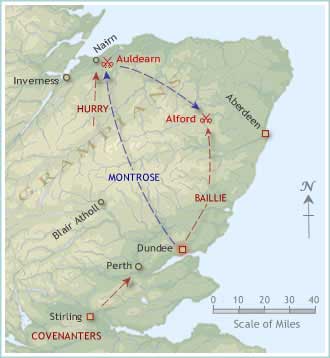

In the spring of 1645, Montrose marched into north-eastern Scotland to rally support for the King while his troops continued to terrorise the Covenanters. He was joined by George, Lord Gordon, the son of the Marquis of Huntly, who became a friend and intimate, though Huntly himself remained jealous of Montrose's growing reputation and regarded him as a turncoat because he had supported the Covenanters during the Bishops' Wars. Lieutenant-General Baillie was detached from Lord Leven's army in England to march against Montrose. During March 1645, Baillie and Montrose manoeuvred in the foothills of the Grampian Mountains, each trying to gain an advantage over the other before committing to battle. This did not suit Montrose's Highlanders, who preferred fighting and plunder to marching. On 4 April, Montrose swept down on Dundee. Gaining entrance through a breach in the crumbling town walls, the Highlanders routed the local militia and set about sacking the town. That same afternoon, they beat a hasty retreat through the eastern gate as Baillie's forces approached from the west. Montrose skilfully manoeuvred to escape the pursuing Covenanters and retreated into the Highlands. |

Covering the routes south to prevent Montrose from threatening Edinburgh, Baillie sent his second-in-command Major-General Hurry into the north-east to ravage the lands of the Royalist Gordons. When Montrose marched northwards to support the Gordons, Hurry withdrew towards Inverness, luring Montrose into hostile territory and gaining reinforcements from local levies recruited by Covenanter lairds. Meanwhile, Baillie was marching up from the south, burning and plundering Royalist territory as he went, intending to catch Montrose between the two Covenanter armies. On 8 May, Montrose's army of around 2,000 men made camp at the village of Auldearn near Nairn. Major-General Hurry, with 3,500 Covenanter infantry and 400 horse, made a rapid night march in damp and misty conditions hoping to catch Montrose in a surprise dawn attack on 9 May. It was fortunate for Montrose that Hurry's soldiers fired their muskets to clear damp powder, thus giving warning of their approach. Montrose quickly deployed 500 of MacColla's Irishmen and Gordon clansmen on a low hill to the north of the village, placing the royal standard with them in the hope that Hurry would mistake MacColla's position for the main body, which Montrose concealed behind a ridge to the south. A few musketeers were positioned among the cottages of Auldearn and ordered to keep up a steady fire, to give the impression that the village was strongly held. The Covenanters fell into the trap and began marching across marshy ground and up the slope towards MacColla. Unwilling to remain on the defensive, however, the Irishmen attacked prematurely, charging down the slope into the Covenanters. Hurry's leading regiments stood firm and in fierce fighting the Irish were driven back towards the village. Realising that MacColla was in danger of being overwhelmed, Montrose remarked to Lord Gordon that it looked as if all the glory of the day would be MacColla's. Stung into action, Gordon led 250 cavalry in a ferocious charge against the Covenanter right flank. A startled officer, in his haste to get his men to face about, ordered them to wheel in the wrong direction. Gordon's cavalry hit the disordered Covenanter lines at full force, driving their cavalry from the field. Montrose's main body attacked the shattered right flank while MacColla rallied his men and pushed forward at the front. The Covenanter position collapsed under the double onslaught. At least 2,000 men were killed in the battle and rout. Major-General Hurry fought bravely and was one of the last to leave the field. Back at Inverness he court-martialled and shot the officer who had given the faulty order, then retreated with the remnants of his army to join Lieutenant-General Baillie. |

Alford, Aberdeenshire, 2 July 1645 |

Although he had defeated one Covenanter army at Auldearn, the Marquis of Montrose had to overcome Lieutenant-General Baillie's main force before he could move out of the Highlands and into central Scotland. Alaisdair MacColla returned to the west to raise reinforcements while Montrose and Baillie once again spent several weeks manoeuvring across Moray and Aberdeenshire trying to gain a tactical advantage. The two armies finally met early in July 1645 at Alford, twenty miles west of Aberdeen. While Baillie approached from the north, Montrose took up a strong position on Gallows Hill overlooking a ford across the River Don. He placed most of his troops on the reverse slope of the hill out of sight with a small force on the crest in order to encourage Baillie to advance. As Montrose expected, Baillie thought that the Royalist troops were retreating and sent his cavalry across the ford to outflank them. As soon as most of the Covenanter horse had crossed onto the marshy ground on the south side of the river, Montrose ordered his whole army to advance to the crest of the hill. Unable to retreat safely, Baillie was forced to deploy close to the Don in an area of marshy ground, using hedgerows and wet ditches to strengthen his position. Both sides drew up in standard formation, with two cavalry wings and infantry in the centre. Baillie's army had 1,800 foot and 600 horse under the command of Lord Balcarres. Montrose had about the same number of foot but only 300 horse. Lord Gordon's cavalry were placed on the Royalist right wing, Lord Aboyne on the left. In the centre were the Irish foot commanded by Magnus O'Cahan and Highlanders of the MacDonald, Gordon, Graham and Stewart clans, with a small reserve in the rear. The battle started when Lord Gordon charged downhill against Balcarres' cavalry. A fierce fight ensued on the Royalist right wing. Balcarres held his ground until Nathaniel Gordon came up with his infantry to support his kinsman, instructing his men to get among the Covenanter horses and use their dirks to hamstring them. As the surviving Covenanter cavalry broke and fled, the Gordons turned to attack the flank of Baillie's infantry in the centre. Meanwhile, Lord Aboyne led his cavalry down the hill to outflank Baillie on the opposite wing while O'Cahan and the Highlanders charged in the centre. Montrose brought up his reserve to the brow of the hill to give the impression of an overwhelming force and the Covenanter position collapsed. Up to 1,000 men were slaughtered as they tried to escape back across the ford. For Montrose, however, the victory was soured by the death of Lord Gordon, killed by a stray bullet from his own side during the rout of the Covenanters. |

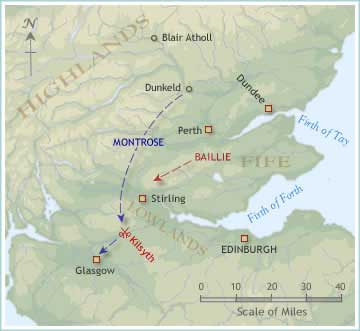

Kilsyth, Stirlingshire, 15 August 1645 |

|

When Alaisdair MacColla rejoined him with more clansmen from the western Highlands, the Marquis of Montrose was able to muster the largest army he had yet commanded of around 3,000 foot and 500 horse. After raiding for supplies in the north-east, the Royalist army advanced southwards towards Perth and established a base at Dunkeld. The Scottish Parliament — driven from Edinburgh by a virulent outbreak of plague to Stirling and then to Perth — resolved to concentrate all available forces against Montrose. New levies were raised in Fife, the borders and south-western Scotland. Although the home army soon outnumbered Montrose's forces, the recruits were untrained and poorly disciplined. Lieutenant-General Baillie offered his resignation after the defeat at Alford and Parliament decided to recall Major-General Monro from Ulster to command all forces in Scotland. However, Baillie was obliged to continue his command until Monro's arrival. Meanwhile, the Committee of Estates, including the Marquis of Argyll, Lord Balfour of |

Burleigh and several leading clergymen, accompanied Baillie on campaign to offer him advice on strategy and tactics. Montrose unexpectedly marched from Dunkeld to cross the River Forth and into the hills south of Stirling. With Montrose now threatening the Lowlands, the Covenanter committee urged an immediate pursuit. Montrose knew that the Earl of Lanark was marching from Glasgow with Covenanter reinforcements, so he turned to fight Baillie before Lanark could join him. Montrose halted his army near the village of Kilsyth between Glasgow and Stirling. He drew up in fields that formed a basin amidst a surrounding ridge of hills. The Covenanters deployed on rising ground to the east of Montrose's position. With a rough slope separating the two armies, Baillie was content to hold his ground and await the arrival of the Earl of Lanark's reinforcements. The Committee was concerned that Montrose might try to escape back into the Highlands so a flanking march was ordered along the hill crests to occupy Auchinrivoch ridge to the north of Montrose's position. This entailed marching the Covenanter army across the front of the enemy. Skirmishing broke out between some of Baillie's leading troops and the MacLean Highlanders who were occupying a group of cottages on Montrose's left flank. The skirmish escalated as Highlanders and Covenanters acted without orders to join the fray. Realising that the Covenanter line had become disordered as Baillie tried to re-deploy in battle order, Montrose sent Lord Aboyne's cavalry in to drive off the enemy horse and expose the infantry on the right flank. With the routing of the horse, the Covenanter infantry started to break and scatter. A few officers tried to rally their troops but the situation was out of control. The line collapsed under the onslaught of Montrose's attack. The last Covenanter army in Scotland was routed and slaughtered. The Committee of Estates fled across the border to Berwick. The Earl of Lanark abandoned his newly-raised levies and joined them there. With no Covenanter army left to oppose him, Montrose was the master of Scotland. He marched in triumph into Glasgow on 18 August 1645. Unable to advance to Edinburgh because of plague in the city, he issued a proclamation at Glasgow to summon a new Parliament in the King's name. |

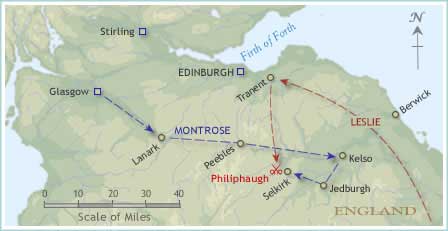

Philiphaugh, Selkirkshire, 13 September 1645 |

|

When the triumphant Marquis of Montrose occupied Glasgow in August 1645 after his string of spectacular victories against the Covenanters, it seemed that he had reclaimed Scotland for the King's cause. The Covenanter leaders fled into England. A meeting of the Scottish Parliament was called for October and members of the Scottish nobility declared their support for Montrose. However, his power in Scotland proved to be illusory. He was distrusted in the Lowlands for his reliance on wild |

Highlanders and Catholic Irishmen; the atrocities perpetrated on Aberdeen the previous year had not been forgotten. Montrose imposed strict military discipline as soon as he entered Glasgow, but this was not to the liking of his men. The clansmen were reluctant to march any further south and began to return to the Highlands. Alaisdair MacColla left for Argyllshire to continue the inter-clan war against the Campbells in the west of Scotland. Lord Aboyne departed with his cavalry when Montrose appointed the Earl of Crawford his General of Horse. Montrose's attempt to recruit new forces were unsuccessful. Deserted by many of his former comrades, Montrose was still determined to march into England to join forces with King Charles. Early in September 1645, he advanced to Jedburgh near the English border accompanied by a small force of 700 Irish infantry and 200 horse. He hoped to recruit another army in the Borders, but troops promised by the Earls of Roxborough, Home and Traquair did not materialise. At Jedburgh, Montrose learned that Lieutenant-General David Leslie with 4,000 cavalry from Lord Leven's army in England had crossed the border and was hurrying to cut him off. Montrose turned around and made for Selkirk, intending to escape into the hills and fight Leslie on his own terms. On the night of 12 September, Montrose and his cavalry quartered at Selkirk while his infantry camped in fields a mile away at Philiphaugh. Montrose's scouts failed to detect the approach of Leslie's cavalry, which attacked the encampment at Philiphaugh out of a dense autumn mist early on the morning of 13 September. Although disorganised, the Irish foot quickly took up defensive positions among the hedges and enclosures. Montrose with some of his cavalry arrived in time to support the Irishmen and two Covenanter attacks were repulsed. However, with overwhelming numbers, Leslie succeeded in outflanking and surrounding the Royalist position. Attacked from all sides, Montrose's small force of cavalry retreated and fled. The Irish infantry surrendered on Leslie's promise of quarter, but the Committee of Estates later ordered the massacre of all the prisoners as well as their camp followers. Montrose remained at large in Scotland for another year. Although he hoped to raise further support in the Highlands, his first major defeat proved decisive and he was unable to pose a serious threat to the Covenanters again. The powerful Marquis of Huntly belatedly raised the Gordon clan against the Covenanters yet refused to co-operate with Montrose so that his intervention was ineffective. Montrose threatened Inverness during the spring of 1646, but he was driven back into the mountains by the approach of Covenanter forces under Major-General Middleton. After the surrender of King Charles in England, Montrose received orders to disband his remaining forces. He negotiated terms for surrender with Middleton in July 1646 and sailed away into exile in Norway on 3 September. |

1650: Carbisdale: Montrose's Last Campaign |

|

When Royalist hopes of uniting Ireland behind Charles II ended with Cromwell's Irish campaign in 1649, Charles turned his attention to Scotland. Earlier negotiations with the Covenanters for military support against the Commonwealth had broken down but by the end of 1649 Charles was left with no option but to seek another treaty. At the same time, he appointed the Marquis of Montrose his Captain-General and commissioned him to raise forces for an invasion of Scotland. Montrose was passionately loyal to the Royalist cause and had been an avowed enemy of the Covenanters since his spectacular campaign against them for Charles I in 1644-5. Charles II planned to use the threat of another campaign by Montrose to coerce the Covenanters. During the spring of 1649, Montrose travelled through Scandinavia, the German states and Poland attempting to raise troops, supplies and money for the Royalist cause, but with little success. Negotiations between Charles and the Covenanter leaders broke down in May 1649 and Montrose was authorised to take military action |

against them with whatever forces he could raise. In September 1649, he sent 200 Danish mercenaries under the command of the elderly Earl of Kinnoul as an advance guard to occupy Kirkwall, the main town on Orkney, while he tried to raise further support in Germany. On 23 March 1650, Montrose himself landed at Kirkwall with around 250 German mercenaries and a small supply of weapons. Montrose's lieutenant-general Lord Eythin remained on the continent with orders to organise a second wave of mercenaries. Montrose was accompanied by his former adversary Sir John Hurry whom he had defeated at the battle of Auldearn in 1645 but who had now changed sides and become Montrose's major-general. Around 1,000 local Orcadians had been recruited to the cause, though the sudden death of the Earl of Kinnoul meant that they had received little training. Upon his arrival on Orkney, Montrose received a letter from Charles informing him that he was to be rewarded with the Order of the Garter, and also that Charles intended to begin a further round of negotiations with the Covenanters at Breda. Montrose was expected to threaten the Covenanters while Charles negotiated with them, but Montrose regarded an alliance between the King and the Covenanters as a potentially disastrous policy. He therefore set out to emulate the campaign he had led in 1644 to raise Scotland for the King. On 9 April 1650, Montrose sent Major-General Hurry across the Pentland Firth with an advance party to secure a route south. Montrose followed with his main force and occupied Thurso where he declared his mission. On 17 April, Montrose summoned Dunbeath Castle in Caithness, which surrendered four days later. Leaving a small garrison at Dunbeath, Montrose marched through Sutherland towards Dunrobin Castle, seat of the earls of Sutherland. Dunrobin was too strong to assault and it soon became clear that there was little local support for the Royalist cause. The Monro, Ross and Mackenzie clans, which Montrose expected to join him, sided with the Covenanters. Meanwhile, Lieutenant-General Leslie mustered his forces at Brechin in Angus and prepared to march against Montrose. Lieutenant-Colonel Archibald Strachan led Leslie's advance guard of cavalry to Inverness. From Dunrobin, Montrose turned inland and marched along the valley of the River Fleet to Lairg where he tried to raise support before turning south to Carbisdale. Behind him, the covenanting Earl of Sutherland advanced to cut off the route back to the north, while Lieutenant-Colonel Strachan moved swiftly up from the south. On 27 April 1650, Montrose's force of 1,200 foot and 40 cavalry took up a strong position on the lower slopes of Carbisdale. Montrose's camp was protected by earthworks and Strachan was heavily outnumbered, having only 200 Covenanter horse, a few musketeers and 400 unreliable Highlanders of the Ross and Monro clans. In the hope of luring the Royalists down from their strong position, Strachan concealed most of his forces in a deep gully, allowing only one company of horse to be seen by Montrose. Assuming that this was all he had to face, Montrose moved forward to give battle. As soon as the Royalists left the protection of the hill, Strachan attacked with the full force of his hidden cavalry. Montrose's Orcadian recruits fled without offering any resistance. The Danish and German mercenaries fell back to the hillside and were attacked and routed by the Monro and Ross Highlanders. Montrose's small force of cavalry fought bravely but was soon overwhelmed. Colonel Hurry was taken prisoner; Montrose himself escaped from the battlefield but was betrayed to the Covenanters a few days later. Both Hurry and Montrose were executed as traitors in Edinburgh the following month. Charles had written to Montrose ordering him to abandon the invasion and disarm his troops because formal negotiations with the Covenanters had begun. The order was sent too late. The King subsequently disavowed Montrose under the terms of the Treaty of Breda, signed on 1 May 1650, in order to secure an alliance with the Covenanters. |

|

This work is licensed under a CREATIVE COMMONS LICENSE |

|

© Paisley Tartan Army 2008-09