THE 1820 RISING |

|

As Wilson mounted the cart that was to take him to the scaffold, the headsman was seated before him, cloaked in black, his face covered, holding a large axe in his right hand and a knife in his left. “Did you ever see sic a crowd as this?” Wilson remarked casually to his executioner. |

|

Beyond this peculiarly Scottish trend of literacy, it must be stated that the major influence on the 1820 Rising is the fact that those involved had lived in an age of revolution for over a generation. The American Revolution of 1776 had already struck a blow to kingship and its attendant system of feudal privileges. However, the French Revolution changed all that for British radicalism, and as William Pitt the Younger led Britain into war with France in 1793, not only did the radicals become more vehement, but the propagation of these reformist ideas came to be viewed by the authorities as sedition, or even treason. In fact by 1795, following the public stoning of King George III’s carriage as it travelled to Westminster, parliament completely redrew the laws for treason, with the effect that holding public meetings in support of reform could lead to the stiffest penalties that the courts were at liberty to dispense. |

|

In the first decade of the 19th century the average wage of a weaver halved, and the devaluation of their work continued in the second decade until the situation became unbearable for many. In 1813, a general strike of an estimated 40,000 weavers lasted over two months, until the authorities arrested the leaders, and unions grudgingly returned to work. As the post-Waterloo recession gripped Scotland, the situation worsened, with 1816 being a particularly black year for Glasgow, resulting in major bankruptcies across the city and its environs. This sparked another gathering of tens of thousands at Thrushgrove near Glasgow, demanding reform. The very next day, King was present at another meeting of important radicals in Anderston in Glasgow. It was also attended by another three men, who are now heavily suspected as being government spies: John Craig, a weaver, Duncan Turner, a tin-smith, and Robert Lees, described only as “the Englishman.” King took the initiative at this meeting and reported that a large-scale rising was imminent and that all those present should make themselves ready for armed conflict. |

| The following day, on March 23, Duncan Turner unveiled plans for a provisional government and revealed a draft of a proclamation, inciting widespread revolt, that was to be posted around the city for the public’s attention. This proclamation is pivotal to the whole history of the rising, and, given that the real Committee for Establishing a Provisional Government was in jail, it seems likely that the proclamation was the work of government agents, and part of larger plan to sink the radical movement in Scotland once and for all. Although it is possible that the committee had managed to release the proclamation from prison, or had drafted it before their capture, the events that followed mounts the evidence against King and his associates, and all points in the direction of government treachery and entrapment. On April 1 1820, the citizens of Glasgow awoke to find the proclamation posted around the city, urging them all “to desist from their labour from and after this day…and attend wholly to the recovery of their Rights…” The proclamation opened with a rousing ideological plea for liberty: “Equality of Rights (not of property) is the object for which we contend, and which we consider as the only security for our Liberties and Lives.” The plea continues to the soldiery, asking if they could really, “plunge…Bayonets into the Bosoms of Fathers and Brothers at the unrelenting Orders of a Cruel Faction…” Strong words, and if the proclamation had been a government plan to draw underground radicals out into the open, they would have perhaps been shocked at the level of response from ordinary people and workers all over West and Central Scotland. |

|

The following Monday, people from many different trades, but especially weaving, stopped work. They were not only refusing to work, but were in many cases preparing for war. Reports flooded in of groups of men engaged in military drills, and making weapons such as pikes from any material that could be obtained. Revolt was in the air. Waiting in Condorrat was John Baird, at the head of five men, holding his half card that had been given to him by none other than John King in one of his many guises. Both Hardie and Baird were no doubt expecting to unite with a small army when they matched their cards, and were obviously disappointed when they did match cards in the early hours of the morning. However, John King promised more support before they reached Carron, and he himself would ride ahead to rally these supporters. |

|

The ensuing battle was nothing more than a skirmish, whereby Hodgson’s force of 32 soldiers, after a volley of shots from the radicals, easily overpowered them with a cavalry charge. Two soldiers and four radicals were wounded. In total, 19 of the radicals were taken prisoner and sent to Stirling Castle. Also on April 5th, the awful fate of James Wilson was starting to unfold. Again, one of our suspected spies was involved, this time the “Englishman” Lees, who sent a message to the Strathaven radicals that the rising had started. Wilson left with a small force of 25 the following morning, carrying a banner that declared “Scotland Free or a Desert.” |

| The government’s retribution was as harsh as the not-always-unsympathetic juries would allow; but examples had to be made, and they took the form of the executions of Wilson, Hardie and Baird. The rising was over, but the radical movement was only in an early stage of its evolution. To some, the whole episode may appear minor and of little historical importance in comparison to other Scottish rebellions of earlier centuries; however, the rising must seen in the context of reformist, radical and revolutionary traditions. Ordinary people from all over an increasingly industrial Scotland had been inspired to rise and overthrow the state in order to secure their rights and better working conditions. The 1820 Rising must be seen as a prototype of the mass movements that would gather under the |

|

| Chartist or socialist banners later in the century and into the next. Along with the Peterloo incident, it marks an intensification of the desire and need for reform, and the martyrs, Wilson, Hardie and Baird, would serve as examples to those who feared that nothing could be done in the face of such as an increasingly powerful industrial state. |

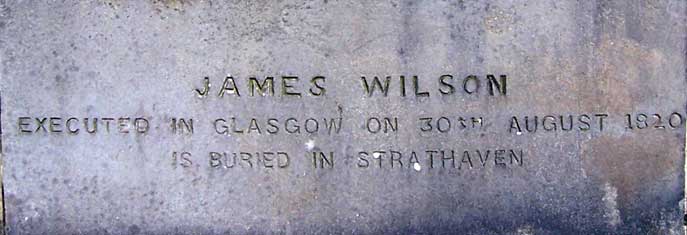

James Wilson: "The Strathaven Martyr" |

"I am glad to hear that my countrymen are resolved to act like men. We are seeking nothing but the rights of our forefathers - liberty is not worth having, if it is not worth fighting for. " April 1820 |

James Wilson was a weaver, an artisan, an educated man. He died in 1820. Born in 1760, he lived during a period when the poor were without liberty or guarantees of life; when all expressions of desire for change and every aspiration towards democracy were ruthlessly crushed. Wilson has been a radical all his life. He has been prominent in the Friends of the People, set up in the 1790s to achieve political reform. After the Napoleonic Wars, there was an economic slump. The country was seething with rebellion. The government decided to act by flushing out leading radicals. Wilson was to be caught in their trap. |

|

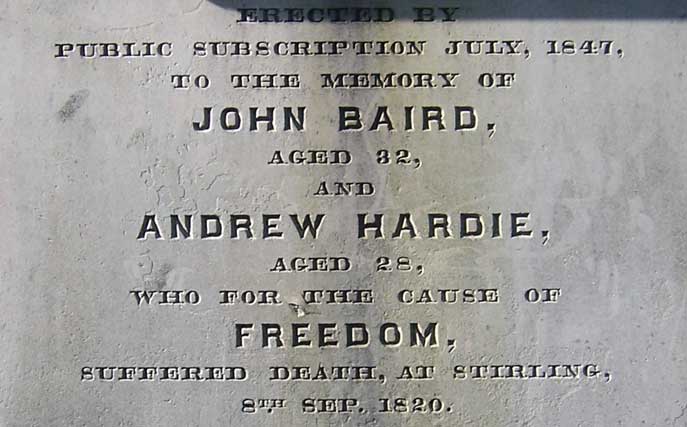

John Baird and Andrew Hardie |

My suffering countrymen! I remain under the firm conviction and I die a Martyr in the cause of Truth and Justice, and in the hope that you will soon succeed in the cause which I took up arms to defend. Andrew Hardie August 1820 |

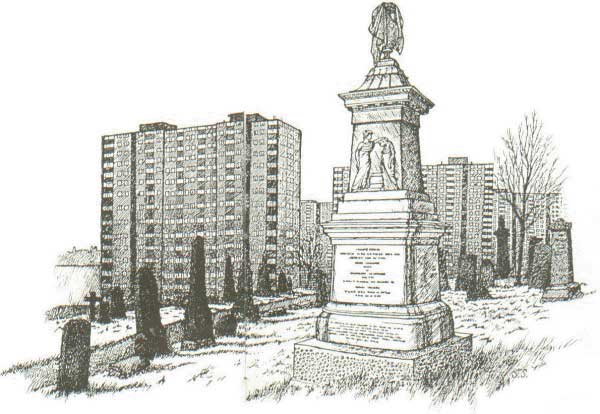

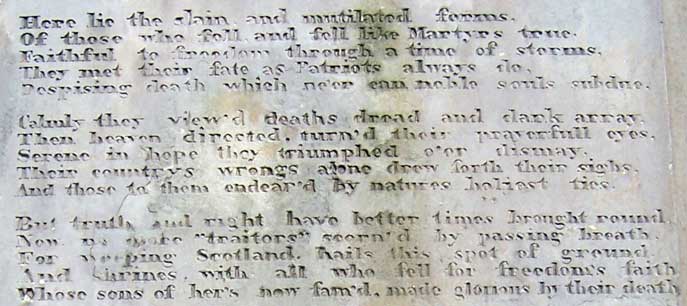

John Baird was born on September 1, 1790. A weaver by trade, he was brought up in the village of Condorrat. Baird had a military career in the British Army, serving in the 2nd Battalion of the 95th Regiment of Foot (known as the Rifle Brigade) seeing military action in both Argentina and Spain. His military experience meant that he was suitable to become commander of the Radicals in their doomed march to the Carron Ironworks. He was sentenced to death and was executed in Stirling on September 8, 1820 along with Hardie. After their unlawful execution their dismembered bodies were buried in a single grave outside Stirling Castle, where they remained for 27 years. It was then decided by Glasgow Radicals to give them an honourable burial. A party of Radicals travelled from Glasgow to Stirling to find the grave, but the grave was unmarked. However an old man named Thomas Chalmers, pointed out a particular spot claiming this to be the grave. After much doubt and considerable digging they came upon the bones of two bodies. The old man had been accurate in his pinpointing the spot as the bones could be identified by the smashed jawbone of Baird caused by the headsman missing his target first time. They were disinterred and reverently buried in Sighthill Cemetery in the north of Glasgow and an inscribed monument erected by public subscription. |

|

For More Info On The 1820 Risings See Below. |

|

© Paisley Tartan Army 2008-09